The Library of Congress name authority file prefers Charles Haslewood Shannon, listing the alternative names C.H. Shannon and Charles Hazelwood Shannon.

Shannon's father called him Charles Haslewood, and he must have been right...

The name is thus written in the Quarrington Parish Records - Baptisms (1862-1863). We can assume the Church official made no mistake at the time. After all, it's much more unusual than Hazelwood.

|

| Quarrinton Parish Records (on Lincs to the Past) |

Shannon himself signed his work with the names C.H. Shannon or Charles Shannon. However, when his middle name was added, it is 'Hazelwood'. Did he prefer that spelling?

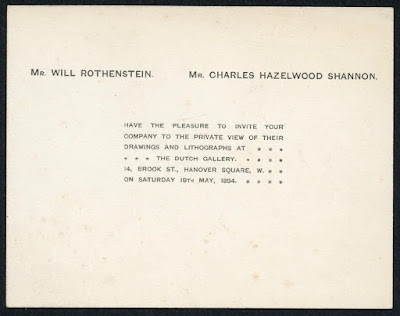

This middle name appears, for example, on an invitation to an exhibition of drawings and lithographs at The Dutch Gallery in London in May 1894. The card states that 'Mr. Will Rothenstein' and 'Mr. Charles Hazelwood Shannon' have the pleasure of inviting the reader to the private view.

|

| Invitation, The Dutch Gallery (1894) |

|

| The Pageant for 1896 (published 1895): title page |

In short, Charles Shannon was officially called Charles Haslewood Shannon, but as an artist he used the name Charles Hazelwood Shannon.

Postscript, August 2020

Steven Halliwell informed me that Shannon's father had an elder sister, called Elizabeth, who married Charles Baker Haslewood. Her husband died in 1863, two years after they married, shortly before Charles Shannon was born. Halliwell suggests that he was given the middle name after his father's brother in law.