Emery Walker - see previous blog - played an important advisory role for private presses in the 1890s. He inspired William Morris to design his first typeface and advised the Kelmscott Press, had a printing press installed for Cobden-Sanderson and supervised the production of the Doves Press for many years, St. John Hornby (Ashendene Press) wrote that Walker was 'a mine from which to draw a wealth of counsel', and Walker advised Harry Kessler (Cranach Presse). In the same breath it is often said that he also advised Charles Ricketts and the Vale Press.

|

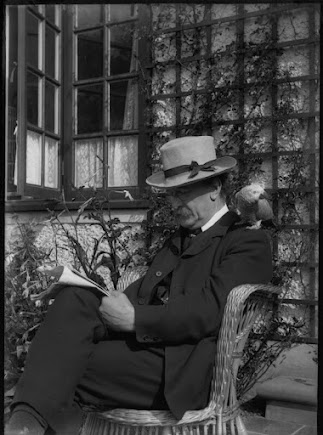

Sir Emery Walker Unknown photographer Modern bromide print, circa 1890 © National Portrait Gallery, London [NGP x200016] |

This is restated in the reconstruction of Walker's lectures, Printing for Book Production: Emery Walker's Three Lectures for the Sandars Readership in Biblography, edited by Richard Mathews and Joseph Rosenblum (2019):

Walker helped Charles Ricketts with the Vale Press in Chelsea [...]'.

The assertion is seen as a commonly known fact that can do without a footnote. But actually, that footnote would remain empty: there is no known source for this claim.

The earliest possible reference, as far as I can determine, is from 1938, when both Walker and Ricketts were already dead. Greta Lagro Potter wrote: 'Emery Walker was a friend of Charles Ricketts of the Vale Press where the same ideals are expressed.' (An Appreciation of Sir Emery Walker’, The Library Quarterly, July 1938, p. 409.)

This friendship was later redefined as a relationship of adviser and pupil, see Charles B. Russell who suggested that Ricketts and Walker were collaborators. ('Cobden-Sanderson and the Doves Press', Prairie Schooner, Fall 1940, p. 181): 'Walker also helped to design the "Subiaco" type of the Ashendene Press under the direction of St. John Hornby. Later on he went with Charles Ricketts of the Vale Press.'

Later it was presented as fact, as in Rookledge’s International Handbook of Type Designers by Ron Eason & Sarah Rookledge (1991, p. 164) where Emery Walker was mentioned as adviser to the Vale Press after 1908 (The Vale Press ceased to exist in 1904!).

Ricketts and Walker did know each other. Walker, for example, visited Ricketts and Shannon on 9 December 1897. He was then in the company of Sydney Cockerell who apparently met Ricketts before, but not Shannon. Cockerell noted in his diary:Then with Walker to 8 Hammersmith Terrace where I met Shannon & Ricketts. Liked Shannon, whom I had not met before, very much.

(See William S. Peterson, Morris & Company. Essays on Fine Printing, 2020, p. 100-101).8 Hammersmith Terrace was the address of May Morris, the daughter of William, who was often visited by Ricketts. Ricketts's diary note for 7 March 1902, for example, mentions: 'Dined with Miss Morris. Emery Walker turned up afterwards and told us amusing details of the decoration schemes for the Coronation [...].'

Walker also owned some books from Ricketts's Vale Press which now reside with the Emery Walker Library at The Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum. On 17 July 1899 Ricketts gave him a copy of A Defence of the Revival of Printing, which had just appeared.

But all indications are that Ricketts and Walker did not know each other when the Vale Press was founded and that the issues of The Dial were not given to him when they appeared, but only later.

Most importantly, however, Ricketts did not need Walker's advice. Unlike Morris, Cobden-Sanderson and Hornby, he did not have a printing press at home. His books were set by hand and printed on a hand press by expert staff at the Ballantyne Press. If Walker had played a part, Ricketts would have mentioned him in his bibliography, where he mentions the punch-cutter Prince and the engraver Keates (misspelled as Keats) and showed his gratitude:

My books would not have achieved that measure of technical success in "build" and presswork had I not benefited by the untiring energy and the intelligent sympathy of Mr. Charles McCall and of his son, C. Home McCall. It will remain known only to ourselves the tact and patience it has required to secure the success of a printed border, or even a mere page of type with an initial, not to mention those books with recurring woodcuts. (A Bibliography of the Books Issued by Hacon & Ricketts, 1904, p. xvii-xviii).