A separate section within James Dunn's collection, whose core consisted of the eighteenth-century illustrated books and rococo prints, comprised a collection of modern private press editions. He owned a few volumes published by the Nonesuch Press, and acquired a copy of the Eragny Press edition of C'est d'Aucassin et de Nicolette (1904) with colour wood engravings by Lucien Pissarro. This was the last book that Pissarro printed in Vale type (designed by Charles Ricketts). From then on he used his own Eragny type.

Gradual donations

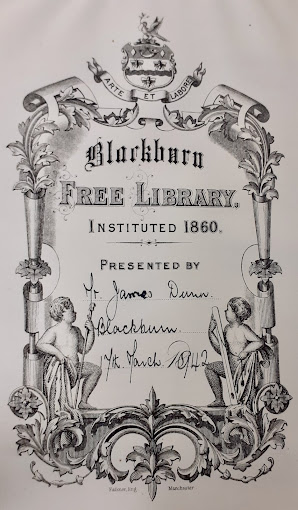

Judging from the labels pasted by Blackburn's library in the books donated by Dunn, Ricketts's Vale Press editions arrived not all at once, but in five batches.

|

| Label in Vaughan's Sacred Poems (1897) (James Dunn Collection, Blackburn) |

In November 1940, he donated two Vale Press editions: Vaughan's Sacred Poems (1897) and Meinhold's Mary Schweidler, the Amber Witch (1903), an early Vale Press edition in octavo and a later edition in quarto.

The second batch consisted of three works, registered by the library in April 1941: Landor's Epicures, Leontion and Ternissa (1896), Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (1900), and Ecclesiastes, or The Preacher, and the Song of Solomon (1902). Again, a mix of earlier and later works from the Vale press, all text editions without illustrations. The first volume of the Shakespeare edition did have an illustrated opening page and decorations in the margins (like all volumes).

Two more gifts followed that same year: The Poems of Sir John Suckling (1896) and T.S. Moore's Danaë (1903). The last book contains three wood engravings by Charles Ricketts.

Then, on 17 March 1942, three more Vale Press editions from Dunn's collection arrived at the library: John Gray's Spiritual Poems (1896), Arnold's Empedocles on Etna (1897), and The Parables from the Gospels (1903). The second book features no illustrations, the first has a wood-engraved frontispiece by Ricketts, while the third book contains no less than ten wood-engravings.

Finally, on 14 April 1942, follows The Kingis Quair (1903).

|

| Label in The Parables from the Gospels (1903) (James Dunn Collection, Blackburn) |

Can we infer from this that Dunn's favourite Vale Press books were the illustrated editions? Perhaps so, but then we must also note that a number of important illustrated volumes are missing, such as the two editions of Apuleius's story of Cupid and Psyche with illustrations by Ricketts or the Wordsworth edition with woodcuts by T.S. Moore.

A Selection of Vale Press Books

What we do know with certainty: James Dunn did not (probably could not) aim for completeness. He owned eleven books from the Vale Press from the years 1896 to 1903. He did not buy the concluding bibliography, nor did he own the Vale Press's programmatic books, Ricketts's A Defence of the Revival of Printing, or (a collaboration with Pissarro) De la typographie et de l'harmonie de la page imprimée, even though this was the Vale Press's only French-language publication, somewhat of an open invitation to a Francophile.

Clearly, he did not subscribe to the Vale Press editions and it is not unlikely that he acquired these works much later, antiquarian, and thus only when the opportunity arose. Michael Field's plays (four in total) are absent, as are editions by Tennyson, Keats, Shelley, Browning and other literary luminaries. Of the 39-volume Shakespeare edition, he owned only the very first volume, Hamlet.

|

| Spine (detail) of Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (Vale Press, 1900) |

Thanks are due to Mary Painter, librarian at Blackburn Central Library, for providing the scans of Vale Press books from the library's collection.

Next week: more about James Dunn as a Vale Press collector.