[Continued from last week's blog about the artist and collector Emilie van Kerckhoff:]

In 1897 - aged 32 - Emilie van Kerckhoff was one of the major contributors to modern book art for an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

|

| Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (c. 1895) |

This was a wide-ranging book exhibition, displaying works from all periods and countries. The (novel) attention for the modern book was mentioned by several newspapers. A trade journal of typographers, Ons Vakbelang (Our Trade Interest), published a report that mentioned her name in relation to the rooms that were devoted to modern books:

Contemporary books also were on display [in this room], especially a fine collection of Kelmscott Press editions, submitted by Mrs. Emilie van Kerckhoff, from The Hague.

(Ons Vakbelang, 15 August 1897)

The publishers Van Gogh (Amsterdam) and Edmond Deman (Brussels) had also submitted works for this section.

From this reference we know that she was one of the earliest collectors of the Kelmscott Press in the Netherlands, and certainly the first female collector.

That she had money to spend on books is also evident from another special copy in her collection, an example of Dutch art nouveau, one of ten copies printed on Japanese paper of La Jeunesse Inaltérable et la Vie Eternelle (1898) [dated 1897]. This modern deluxe book contained etchings by Marius Bauer and etched head and tail pieces by G.W. Dijsselhof. In February 2008, this particular copy was auctioned at Sotheby's with the Schiller-David collection in which it had ended up.

|

| Emilie van Kerckhoff's copy of La Jeuness Inaltérable et la Vie Eternelle (Sotheby's) [details of cover and of bookplate on endpaper] |

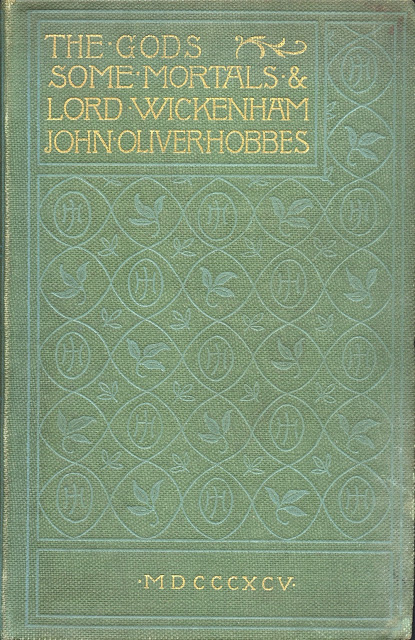

But Emilie van Kerckhoff also owned (at least) two books designed by Ricketts: she possessed a copy of The Sphinx (mentioned in , but she also owned a copy of Christopher Marlowe's Hero and Leander, with wood engravings by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, bound in parchment (this copy was offered for sale in 1994, see catalogue 50, Die Schmiede). These books represent, it is thought, the tip of the iceberg of a collection that was both contemporary and rich, and, moreover, owned by a single-minded Dutch woman.

|

| Oscar Wilde, The Sphinx (1894) Cover design by Charles Ricketts Emilie van Kerckhoff's copy |

Perhaps, these books may be a key to her own book and bookplate designs. Recently, Leiden University Library acquired a unique portfolio designed by Van Kerckhoff, apparently for her own use. (See Kasper van Ommen, 'Friends of Leiden University Libraries generously support acquisitions for the Nieuwe Kunst collection', Leiden Special Collections Blog, June 25, 2020The binding is divided into several bays by double lines in gold and is decorated with floral motifs in light and dark blue. The initials on the front cover are further decorated by five small circles and two stars in gold and small brown dots. The back of the binding is less exuberant in decoration. The decoration is most likely to be influenced by the work of Nieuwenhuis, who designed several similar luxury objects.'

|

| Portfolio designed by Emilie van Kerckhoff (Leiden University Library) |