The final episode on the provenance of the copy of Daphnis and Chloe in the collection of Arizona State University Library deals with the older bookplate of Charles Plumtre Johnson that was pasted into the book first, and later partly covered by Sperisen's ex libris (see blog 550) and Ricketts's postcard to Walker (see blog 549).

|

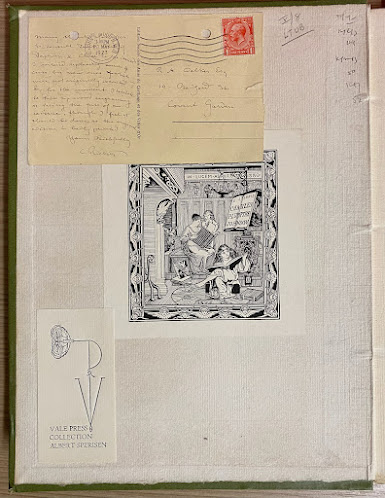

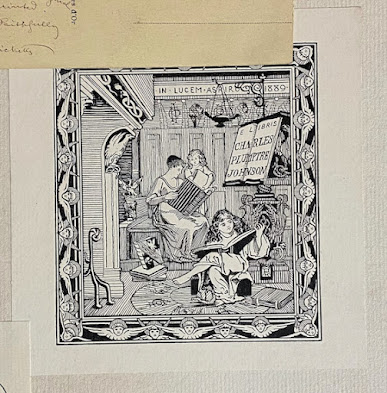

| Arthur Robertson, Bookplate for Charles Plumptre Johnson (1889) |

It is a rather nineteenth-century image, dated 1889, in which various neo-styles evoke the atmosphere of a cosy spacious reading room with fireplace, an oil lamp attached to a lectern with the ex libris inscription, a seated woman, a standing child, and a relaxed girl, all handling rather large-format books. To the left and right, books stand and lie, displayed, stacked or set aside.

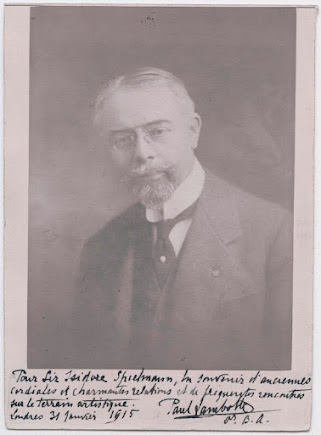

The ex libris, signed with the initials 'AR', was drawn by the artist Arthur Robertson (1850-1911). [Brian North Lee wrote an engaging article about him for The Bookplate Magazine of March 1992.]

Fortunately, the name of the book's original owner has been given the less common middle name of Plumptre. Charles Plumptre Johnson can be identified quite easily as the son of Sir George Johnson (1818-1896), Physician-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria.

Charles Plumptre Johnson (1853-1938) was a yachtsman - for his yachting career see Maritime Views. However, he was also a bibliophile, a bibliographer of note, and an author of several books on collecting first editions of Dickens and Thackeray. Educated at Marlborough and matriculated at the London University in 1872, he was admitted a solicitor in 1876. At the end of his professional career, he was a director of the Law Fire Insurance Society. |

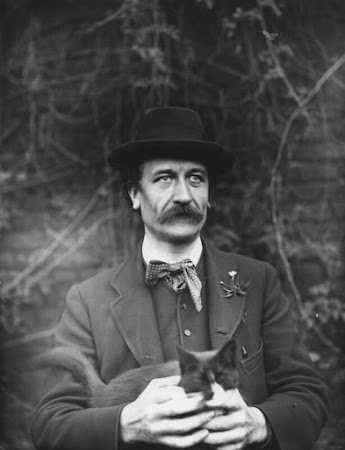

| Charles Plumptre Johnson by Bassano Ltd, whole-plate glass negative, 20 April 1921 [National Portrait Gallery: NPG x120938] (Creative Commons License) |

He was a member of the Sette of Odd Volumes as early as 1891 and inscribed copies of this bibliophile society's publications are now in the Norman Colbeck Collection. He collected modern literary works, water-colours and prints of boats, and he donated his collection of Gilbert and Sullivan, including manuscripts, to the British Museum. Given in 1935, the collection was exhibited in the King's Library in 1936.

But there must have been an earlier auction of his library. Bookseller and collector Norman Colbeck (1903-1988) remembered this in 1968: