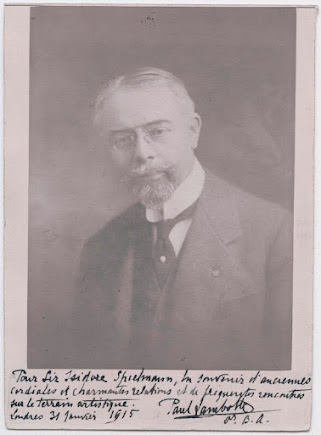

Blog 552, The Wise and Foolish Virgins by Charles Shannon, promised more information about Joseph Bibby's acquisition of Charles Shannon's painting that eventually was given to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

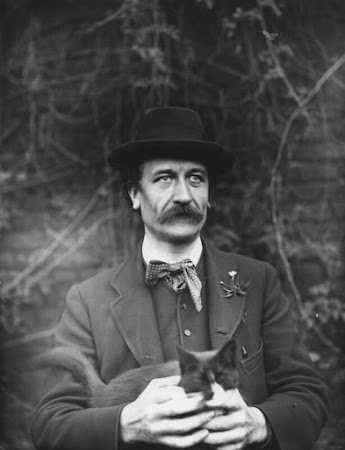

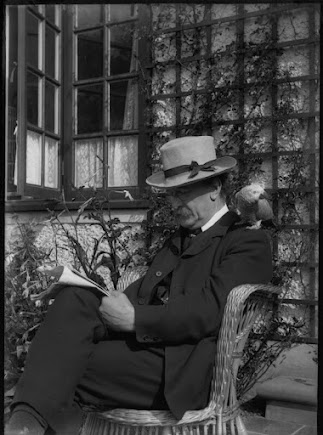

Joseph Bibby (1851-1940), devoutly raised as a Methodist, was an English industrialist who, together with his brother James, built an empire around cattle fodder and Bibby's Pure Soap in Liverpool. James was the businessman, Joseph indulged in marketing and publicity. He was a generous benefactor of social causes. He developed an interest in theosophy and became a vegetarian.

|

| Cover of Bibby's Annual (1921), with an illustration by Ernest Wallcousins (detail) |

Part of his advertising campaigns was an annual magazine, Bibby's Annual (1906-1922, 1938). He also published Bibby's Quarterly, Bibby's Almanac, and The Bibby Cake Calendar. He edited and subsidized the issues of Bibby's Annual that integrated theosophy with art and literature, incorporating plates after famous paintings and prints by Rembrandt, Reynolds, Dürer, Velasques, Gainsborough, Turner and Blake. Works by lesser-known modern artists, such as William Orpen and Charles Shannon, were also illustrated.

A lithograph and a painting by Shannon were reproduced in the penultimate volume, 1921. The lithograph 'Tibullus in the House of Delia' received a short introduction which, together with the image, was given a corner in an article on 'The Source of Social Wellbeing':

Mr. Shannon is a master of the art of lithography, which, since the renewal of interest largely due to Mr. Whistler, is no longer regarded as a poor relation of the Graphic Arts. He is a poetic and subtle draughtsman, an absorbed student of beauty, a seeker after nobility of design who subordinates literary to pictorial requirements. For this reason it is vain to seek in our picture more than the slightest literary motive. "Delia" may be the lady referred to in Pope's lines - "Slander or poison dread from Delia's rage" - but we do not know. What seems suggested is one of those sinister beauties of the Renaissance, whom men admired and feared. we see a banquet where the guests are raising wine cups in her honour, while one whispers in her ear. It is just a fancy in which the artist has expressed his power of noble and rhythmic design. The subject was once admirably characterised by Sir Frederick Wedmore as "ideal and opulent and Titianesque."

The art-historical text and lithography are embedded in the world of theosophy. Already on the first page, above and below the table of contents, there are quotations from L.W. Rogers, long-time president of the Theosophical Society in America: 'Man is a God in the making. Latent within him are all the attributes of divinity.'

|

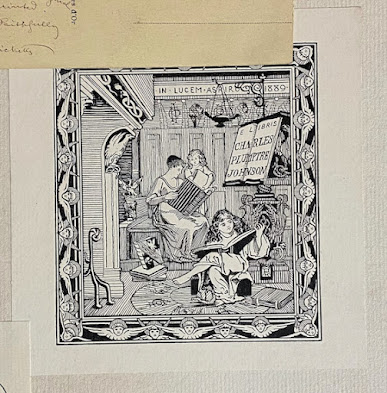

| Charles Shannon, 'The Wise and Foolish Virgins' (1919-1920) [detail] Walker Art Gallery (National Museums Liverpool) |

Opposite the page with Shannon's lithograph is a full-page colour image, printed across, of Shannon's 1920 picture 'The Wise and Foolish Virgins'. Joseph Bibby must have purchased the oil painting in 1921 and immediately decided to use it for his annual because of its religious subject. The accompanying text is long, and we may assume that it was written by Bibby himself:

Mr. Charles Shannon is one of the most sensitive and distinguished of living artists. His art is the quiet product of study and dream; standing aloof from haste or turmoil or anything suggestive of sensation or notoriety. It reaches a region of pure beauty, beyond the world of reality or actuality; where mere events lose much of their significance, and cries of passion and emotion are but faintly heard. The theme of the "Wise and Foolish Virgins" has appealed to him solely from the point of view of the creation of pictorial beauty. His picture is frankly not very scriptural. We are not here much concerned with the Twenty-fifth Chapter of St. Matthew. This is no vision of sudden midnight alarm; of desperate appeals for what could not be spared; of the tragic doom that may befall innocent and well-meaning souls who lack forethought. The very choice of the banks of a river as the scene puts the Scriptural narrative far away; for what could the Virgins we know be doing there? If, however, we do not have a satisfying illustration of a familiar story, we get instead a noble picture. We think it was the rhythm of the interlacing figures, the haunting beauty and mystery of the night, with its fine yet austere harmony of colour that the artist aimed to achieve; and we gladly admit he has succeeded. Many an earnest thinker has pondered over the true inner meaning of this story, although its lessons of ready preparedness is obvious to all. This story of the coming of the bridegroom has in it a still deeper meaning to the devout mystic, who senses a parable of initiation, the first unfolding of the Divine super-consciousness within, which shall thereafter irradiate and illumine the whole of the inner and outer life. We cannot tell how near that moment is just when it will come, any more than a flower knows the moment when the glory of the universe will burst upon an opened heart that has at last unfolded. But it has to be watched for, prayed for, lived for; since until it comes a man lives but a darkened, divided life, seemingly cut off in consciousness from the true source of his happiness and power. So the lamp which shall light us to that supreme consummation is the vessel of consecrated thought and deed, and it must be filled always with the oil of human service, elsewise it were empty and useless indeed. To those whose light within is thus kept steadily trimmed and burning, there comes the day of Initiation, the reception at the marriage feast, and entrance into the joy of their Lord. The story also indicates that all ignorance and neglect invite a just nemesis.

So, after Bibby has detailed that this subject probably has no religious significance for Shannon - on the contrary - the explanation takes a turn towards pure theosophical thought halfway through, with which the painting ceases to exist as a work of art and becomes only a secondary illustration of a sermon-like story.