|

| Charles Shannon, 'Portrait of Charles Ricketts, painted at Kennington Road, Lambeth', before 1900 |

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

578. An Early Portrait of Charles Ricketts by Charles Shannon?

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

577. A Summer Anthology (6): Sun Burnt a Bright Pink

In February and March 1905, Ricketts and Shannon enjoyed vacations in Rome and Florence, and in August of that year they kept it closer to home. They bivouacked on the English coast for a prosaic reason: their house at Lansdowne Road was being painted. Their accommodation was The Albany Hotel, that curves around Robertson Terrace in Hastings. The hotel had opened in 1885 under the name Albany Mansions.

|

| Albany Mansions, c.1890 |

Charles Ricketts to Michael Field, 1 August 1905

"Choose a friend as you would a book" – I have this on the tip of my pen as I spent quite a considerable time in spending 1 & 6d on a book this morning, at the local library, fixing finally on Emerson’s Essays, a purchase which I now rather regret. I had exhausted tedious spectacled Suetonius whom I had bought in a new translation. I quite understand St Augustine’s defence of him, this author whom I confused with the great Tacitus is a transparent journalist of the oh fie! oh my! type and now, would write for the Standard, which Shannon is now reading – the rest of his time is spent in pretending to read the great Bernhard, Bernhard Shaw that is, not the other, though both are moralists in disguise.

I am just now quite great at whitewashing the C[a]esars, only one seems to have been really bad & a monster & that is Calligula [sic] who reminds me of Michael. On my return I shall look up Tacitus.

I send you a sea greeting

The Painter

This place is a long stretch of seafronts some miles long, steady & continuous like the Earthly Paradise of W. Morris but not quite so monotonous.

|

| The Albany Hotel, 1906 |

Thanks are due to John Aplin for providing the transcription of this letter.

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

576. A Summer Anthology (5): Cold Beer

During the summers, art historian Mary Berenson, who lived with her husband Bernhard Berenson at Villa I Tatti near Florence, visited her mother in London, and during her 1904 stay she visited Charles Ricketts.

|

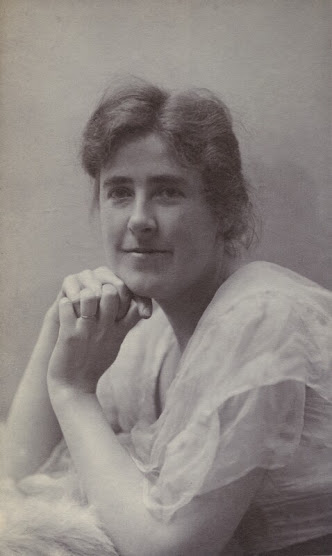

| Mary Berenson by unknown photographer: (matte printing-out paper print, circa 1893) [© National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG Ax160669] |

Charles Ricketts to Michael Field, 29 July 1904

Dear Mrs B.B. called dressed in pale blue and looked like fresh bunches of forget-me nots (plenty of bunches). She is a charming woman from whose presence emanates a perfume of kindness. We mildly ran you both down – oh not very much! – just enough to feel comfortable. I have been basking in the heat & feeling very fit.

We dined with Toby & Tobie’s wife, Fry was there: on his face shon[e] the reflected glory of the house of Lords, he had been all day at the Chantrey commission, we sat in the garden & talked about the inconveniences of travel. Oh that I had the wings of a dove! I should now be drinking cold beer in Dresden.

Roger Fry had been an acquaintance of Ricketts and Shannon since the mid-1890s, and when they moved to Beaufort Street they became his neighbours, but a deep friendship did not develop, even when Fry and Ricketts became involved with the art magazine The Burlington Magazine. They took opposing views on Post-Impressionism.

Thanks are due to John Aplin for providing the transcription of this letter, and for solving the puzzle: Mr and Mrs Toby are nicknames for Thomas Sturge Moore and his bride Maria Appia.

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

575. A Summer Anthology (4): The Heat is Noble

Ricketts and Shannon visited Venice at least three times, beginning in 1899, then in 1903 and in 1908; on the latter occasion staying at the House of Desdemona on the Grand Canal owned by their friends Edmund and Mary Davis, and more commonly known as the Palazzo Contarini Fasan.

|

| Paolo Salviati, photo of Palazzo Contarini Fasan, c. 1891-1894[detail] [Boston Public Library: William Vaughn Tupper Scrapbook Collection] |

It would not be their busiest holiday; there was plenty of idling and lazing around, as a letter to Michael Field indicates.

Charles Ricketts to Michael Field, 20-21 May 1908

[British Library Add MS 58089, ff 93-5]Dear Poet

[...] We passed through a northern Italy empty of field flowers but agre[e]able with tall green corn and grapes of white Accassia [sic], this is splendid this year and saturates the Lido where we go to bask in steady after lunch boredom every day. The heat is noble and the air superb. I like the Palazzo immensely and we shall stay on here after the departure of our hosts, – that is if Shannon is still of the same mind. We shall lunch at the Guadri [sic] and dine among the trees at the Lido, which is a vulgar place.

[...]

Note

Thanks are due to John Aplin for providing the text of this letter.

Wednesday, August 3, 2022

574. A Summer Anthology (3): The Torrid Heat

On August 9, 1911, a heat record was set in the United Kingdom: a temperature of 36.7 degrees Celsius was recorded for the first time in history. The previous letter in this summer series (Purgatorial London) was set during the same heat wave, but focused on domestic scenes. In this letter, the world beyond is brought in.

|

| Louis Béroud, 'Mona Lisa au Louvre' (1911) [Wikimedia Commons] |

The letter is addressed to Mary Davis, artist and wife of Edmund Davis who had commissioned the building of Lansdowne House for a number of artists including Ricketts and Shannon. It was from this flat that Ricketts wrote the letter to Davis, who was apparently traveling and thus provided with Ricketts's version of some news.

A lot had happened.

On July 20, the newspapers reported that Herbert Trench had resigned as director at Haymarket Theatre. There were many strikes that year, including those of railroad staff, which brought transports to a standstill, caused shortages in stores, which caused prices to rise, and drove housekeepers to despair - like Ethel, the loyal servant of Ricketts & Shannon (who continued to work for them until 1923). On 18 August, the House of Lords was forced to pass a new Parliament Act to curb its power. On 21 August, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre; on 26 August, reports circulated that the director of the Louvre, Théophile Homolle would be fired, as, indeed, he was, two days later.

Charles Ricketts to Mary Davis, [Late August-Early September 1911]

[British Library Add MS 88957/8, f23]Shannon had to go to some meeting at the R A, at the door he was asked his business and name.

Your name Sir?

Shannon

O, I am Mr Shannon!

Attendant

Note

Thanks are due to John Aplin for providing the text of this letter.

Wednesday, July 27, 2022

573. A Summer Anthology (2): Purgatorial London

The summer of 1911 was hot. Edith Cooper and her aunt and lover Katharine Bradley - their nom de plume was Michael Field - had fled London and were staying in a cottage near Armitage near Hawkesyard Priory, before spending three weeks in Malvern. They enjoyed the attention not only of the prior, but also of the Dominican novices, especially Brother Bruno and Brother Bertrand. In their diary they noted the constant heat, while 'the cedars are loaded with aroma'. Brother Bertrand swam the lake to bring them 'a glorious armful of yellow waterlilies' (see 'The Diaries of Michael Field', August, 1911, at the online edition at Dartmouth College). In one of his letters, Ricketts responds to the company of young men surrounding Michael Field.

|

| Charles Shannon, portrait of Edith Cooper, 1900-1910, black and red chalk drawing, touched with white on brown paper [Birmingham Museums: 1914P246] |

Charles Ricketts to Michael Field, 14 August 1911

My Dear Poet

I wish for your sake the hot wind would cease, even I who am half Salamander have found London almost purgatorial. I hope among the hills it is cooler. I hope the visit of your new young friends was a success, and that the number was the same on their return. I suppose labels were fastened to their necks like the children in school treats to save counting. Shannon grew troublesome and rebel[l]ious the other day with a large desire for a tame Squirrel; the fault was partly mine, as I had been enraptured by a cage of them in the Brompton Road, and my description was the cause of his desire. He left me in the street purchased a squirrel and a lordly cage and became enamoured with a Mongoose. The squirrel (name Carrots) is now in the house, it is so tame, affectionate and so passionately attached to humanity that it has to be covered with a cloth to quiet the nerves. It is very young and greedy, with huge claws, it tests every thing with its mouth, which is its intellect[;] for the first day it found it difficult not to eat our fingers and ears, the face he recognizes as a personality, our bodies are mere landscape stuff, the human hand is merged in its conception of things with nuts, pieces of apple and eatables generally the fingers are viewed as stalks, not quite eatable after all. It accompanies its exercises in its treadmill and about our clothes with little suffering cries of pleasure and is removed with difficulty from our coats and trousers. When you return you must be introduced to Carrots who probably by then will be a married person and settle down in a larger cage. [...] The proposal is on foot to turn Shannon[']s balcony into a menagerie. [...]

Thanks are due to John Aplin for providing the text of this letter.

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

572. A Summer Anthology (1): In Need of a Long Holiday

Heat waves and holiday traffic jams - it's time for an anthology of Charles Ricketts's letters with references to heat, summer and holidays.

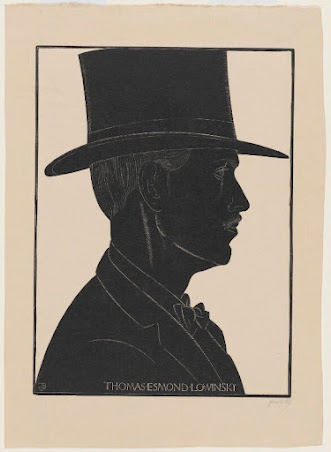

This first letter in the short series was written to artist Thomas Lowinsky (1892-1947), who had attended the Slade School of Art in London before the Great War, and at the time of this letter was serving in the Army of Occupation, stationed in Cologne, before being demobilised in April 1919. The date is uncertain, but the letter probably dates from January 1919. Here are some excerpts from this letter, including a fantasy of a tropical destination.

|

| Eric Gill, portrait of Thomas Lowinsky, 'Thomas Esmond Lowinsky', wood engraving, 1924 [National Portrait Gallery: NPG D5127] |

Charles Ricketts to Thomas Lowinsky, January 1919[?]

I don't know how Cologne stands in the new movement of quite excellent recent German architecture of a neo-classical type, or if any can be seen there; the description of what you have seen suggests the neo-Klinger work of sixteen or more years ago, before quite new elements had arrived – some of them post-impressionistic – which I don't dislike. German work is always over forcible, just as ours is too vague. Even the early masters, Holbein excepted, had this fault. With modern haste and bad taste this overforcefulness is distressing, it hurts the music of Richard Strauss, some of which I like immensely. Apropos of music, the more Russian music I hear more I like it, it is marvellous in its pace, response to sincere and varied emotion and original use of means without German overemphasis or the dryness of the new Frenchmen. I hope you go to concerts and operas; these before the war were first rate in Cologne. The theatre has a stupendous stage over 130 feet deep and a rising and sinking floor for rapid changes. But possibly military etiquette prevents your going – does it? [...]

Poor Philpot is ill. He had a sort of nervous breakdown, his eyes went wrong. He is now in Bath; like all of us he needs sun and a long holiday. I think we ought all to retire to a nice island like Haiti, where the women wear flowers in their hair and have no moral sense, and where we could wear no clothes or bright clothes, canary yellow trousers with pea green spots or else have sun flowers painted on larger portions of our person and coral beads where privacy is desired. I was once shown the photo of a Sicilian boy with a rose petal stuck up – – well, that might be chosen for very hot weather. Davis would of course have to wear thick bathing things covered with camouflage triangles, spots and stripes in the worst modern colouring. We are threatened with coloured clothes; imagine its effect on the city – emerald green spats and flesh coloured or apricot coloured waistcoats and magenta ties. Perhaps it would feel nice and you will see me yet in cobalt or dove colour.

The painter Glyn Philpot (1884-1937) was also a protégé of Ricketts and Shannon.

Ricketts's reference to a photo of a Sicilian boy is remarkable: among homosexuals, nude photos by, for example, Wilhelm von Gloeden were circulating. Lowinsky, himself not a homosexual, probably knew about Ricketts's inclination.

Davis was the name of Sir Edmund Davis (1861-1939), a mining financier and art collector.

Wednesday, July 13, 2022

571. Two Portraits of Charles Ricketts by Max Beerbohm

In 1928 Robes of Thespis: Costume Designs by Modern Artists, a book on modern costumes for plays, revues, operas and ballet, was published. It included seven costume drawings by Charles Ricketts (only one of which was in colour) for 'The Merchant of Venice', 'King Lear', 'The Winter's Tale', and Yeats' 'King's Threshold'. Ricketts was no longer a 'modern artist' in 1928; the hefty book focused on a younger generation. More interesting than the commentary on his costumes is the illustrated introduction by Max Beerbohm.

Beerbohm had lived in Rapallo since 1910, but, he was briefly back in London in 1925. From a taxi, he saw Ricketts and Shannon walking in the street, apparently on their way to the opera:

[...] though I waved my hand wildly to them they did not see me. An any rate, Shannon did not. Ricketts may have, perhaps, and just ignored me. For I was not wearing a top-hat. And Ricketts was.

It was an opera hat - 'a thing that opens with a loud plop and closes with a quiet snap'. Beerbohm remembers the days in the 1890s when he himself always wore a top hat - and Ricketts and Shannon did not. And now that nobody wore top hats anymore, Ricketts did.

I wonder, does Ricketts wear that collapsible crown of his only when he dines out? Or does he, when he comes home, close it with a quiet snap and place it under his pillow, ready for the first thing in the morning? Some painters wear hats when they are working, to shade their eyes. Does Ricketts at his easel wear his gibus?

The answer is no. Rickets painted bare-headedly.

Beerbohm then turns to the use of colour in clothing and laments the fact that since 1830, men's fashion has turned into the tyranny of black and white. Only on stage did the colours shine, at least since 1900, when Gordon Craig and Ricketts designed costumes. Still, the stage designers themselves, walk around in black and white. Beerbohm made a drawing to show it: William Nicholson, Albert Rutherston, Edward Gordon Craig, R. Boyd Morrison and Charles Ricketts - only the last three are shown below.

|

| Max Beerbohm, 'Here are Five Friends of Mine' [Detail] (from Robes of Thespis, 1928) © Copyright of the Estate of Max Beerbohm |

Ricketts, with his reddish beard, stands on the right in a characteristic pose: gesticulating and talking. The others are silent. Beerbohm remarks on this portrait:

I have given Ricketts the small sombrero that I had always associated with him. When one does a drawing, what is one glimpse as against the vision of a lifetime?

Beerbohm understands young people's desire for colour and fantasy and believes that stage designers should set a good example.

I appeal to the designers of theatrical costumes. Doubtless they have hoped that the orgies of colour and fantasy with which they grace the theatres would have a marked effect on the streets, instead of merely making the streets' effect duller than ever by contrast. I suggest to these eminent friends of mine that they should design costumes not merely for actors and actresses, but also for citizens. [...] Let them go around setting the example. This is a splendid idea. I am too excited to write about it. I will do another drawing.

|

| Max Beerbohm, 'Why Not Rather Thus?' [Detail] (from Robes of Thespis, 1928) © Copyright of the Estate of Max Beerbohm |

I just clothed them hurriedly in anything bright that occurred to me. Only once did I pause. I was about to give Ricketts an opera hat of many colours. But this would have been to carry fantasy too far; and I curbed my foolish pencil.

Ricketts now looks like a courtier from the Renaissance, his preferred period, with colourful rings on his fingers, a straight high feather on his cap, a green tunic and tights in blue and white. He also carries a sword.

It is fortunate that Ricketts did not carry a sword in real life.

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

570. Shannon's Drawings for Hero and Leander

|

| Charles Shannon, 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' (woodcut, proof) British Library, London: 1938,0728.9 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

Why Shannon limited himself to this one image is unclear. Of Ricketts's wood-engravings two have four figures and four show only two figures. Shannon's image depicts five figures. To the right: Hermes/Mercury. In the middle: the three Fates, or Moirae (called Destinies in the poem), who are charged with the destinies of living beings, all holding a string: Clotho (the spinner), Lachesis (the drawer of lots) and Atropos (the cutter of the life-thread). On the left is a male figure bearing Mercury's torch.

|

| Charles Shannon, Sketch of Mercury/Hermes for Hero & Leander (red chalk drawing) British Library, London: 1938,1008.31 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

As in the wood-engraving, Mercury raises his hands above his head, wears a short tunic, and holds his caduceus, albeit more obliquely than in the final print. His hat is not included. His winged foot is only sketchily indicated. The tunic has an opening from neck to navel (in the wood-engraving it is a high closing garment.

|

| Charles Shannon, Sketch of one of the Fates for Hero & Leander (red chalk drawing) British Library, London: 1938,1008.30 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

|

| Charles Shannon, 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' (original drawing) [from the collection of Vincent Barlow] |

|

| Charles Ricketts or Charles Shannon, Preparatory drawing for 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' British Library, London: 1946,0209.89 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

Wednesday, June 29, 2022

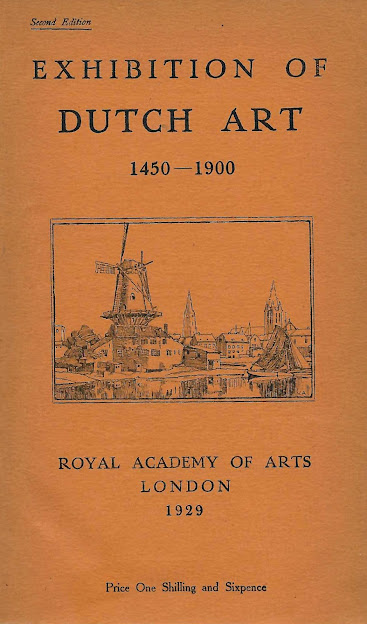

569. Ricketts's Review of the Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450-1900

|

| Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450-1900 (1929: second edition) |

The Dutch Pictures at Burlington House. An Artist's Impressions.

To the average lover of pictures Frans Hals remains the painter of the "Laughing Cavalier" and of the nobler portrait groups at Haarlem, with a dim impression that in his old age the artists attempted something different. It is when Hals refrains from swaggering that he becomes a great master; it is when the cold clarity of his colour turns to grey and his perfect draughtsmanship takes on a more emotional aspect that he touches us most. No. 356 fulfils these conditions﹣we have here more than mere forceful representation; this has become tempered by gravity in mood and a more sensitive vision of life.

Rembrandt fills the big room No. 3. Let us look carefully, and a little wistfully. Most of these masterpieces are here for the last time. They will never be seen together again, save, perhaps, in America, which already holds more than one-third of the master's noblest canvases. What elements in his temper and practice link Rembrandt to the art of his country? Hardly anything, save in his earliest works, where he is influenced by Hercules Seghers and Honthorst in his slightly theatrical rendering of things half imagined, half seen. It is in the rapidly increasing torrent of his practice and, later still, under the stress of sorrow and debt, or yet later, when oppressed by the sordid difficulties of a tragic life, that his art stretched out into the realms of spiritual adventure, that he gains an inward and expressive force which has never been surpassed.

The "Oriental" (No. 169), the "Toilet" (No. 130), the "Man with a Hawk" (No. 98), and the "Lady with a Fan" (No. 99) show the brilliant climax of his early manner.[2]

|

Rembrandt van Rijn and (mainly) workshop, 'Portrait of a Woman with a Fan', 1643 |

Lent by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon

|

| Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450-1900 (1929: second edition), p. 228, No. 589: 'Christ as Emmaus' |

Notes:

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

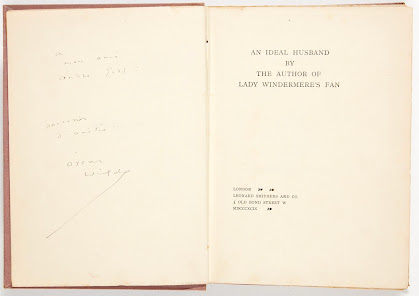

568. André Gide's Copy of An Ideal Husband

|

| Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband (1899): autograph dedication to André Gide |

Many of these will have been signed with a dedication by Wilde. The dedication in Gide's copy reads:

The copy is part of the currently auctioned collection of Pierre Bergé, it is lot 1634 in

The Pierre Bergé Library, Part 6 (Paris, Pierre Bergé & Associés, 6 July 2022). The estimate is €6,000 - €8,000.

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

567. A Portfolio of Woodcuts by T. Sturge Moore (Continued)

Some years ago, Vincent Barlow wrote about an early Vale Press portfolio of woodcuts by T.S. Moore that was so rare that some even thought that, even though it was announced, it had never been published. I mentioned his article in blog 183. A Portfolio of Woodcuts by T. Sturge Moore.

|

T.S.Moore, 'Childhood' (from: A Portfolio of Woodcuts. Metamorphoses of Pan and other woodcuts, 1895) [Image: British Museum, London: 1909,0528.1-10] [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

His article was published in 2014, but since then several catalogue entries and images have surfaced online and it has emerged that the British Museum also possesses a copy [read the description on the museum's website]. Apparently, it had previously been described in an untraceable, impossible-to-find way, but it is now clear that it was added to the museum's collection as early as 1909 thanks to a gift from its creator, Thomas Sturge Moore.

Portfolios can be obtained from C.H. Shannon, 31 Beaufort Street, Chelsea; or from E.J. van Wisselingh, The Dutch Gallery, 14 Brook St., Hanover Square; or from Durand Ruel, 16, Rue Lafitte, Paris.

|

T.S.Moore, 'Pan a Cloud' (from: A Portfolio of Woodcuts. Metamorphoses of Pan and other woodcuts, 1895) [Image: British Museum, London: 1909,0528.1-10] [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

Wednesday, June 8, 2022

566. Charles Shannon's Portrait of Ronald Firbank

One of my favourite writers, Ronald Firbank (1886-1926), who died before he turned forty, was the subject of portraits by a number of famous modern artists in the early twentieth century. One of the first, if not the first, was Charles Shannon who made a pastel of him in 1909.

It was first published on the dust jacket of Firbank's last novel, which appeared posthumously due to delays in publication. Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli appeared in June 1926 - the year of publication was corrected in ink on the dust jacket.

|

| Charles Shannon, pastel portrait of Ronald Firbank (1909), published on the dust jacket of Ronald Firbank, Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli (1926) |

This undated portrait is signed with the initials 'CS'. The current whereabouts of the original portrait are unknown.

No letters or accounts of the meeting between artist and sitter have survived, and we must make do with second or third-hand testimony.

Oscar Wilde's son, Vyvyan Holland, came of age in November 1907 and Robert Ross organised a dinner -party for him. Among the twelve guests were Ronald Firbank, Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon. It was probably the first time Shannon and Firbank had met; the former came from the artistic circles around Ross, the latter from Holland's Cambridge student life.(1)

Firbank was, as Miriam Benkovitz wrote, 'very much concerned with his appearance', and in an attempt to preserve his youth, he had his portrait captured by a series of artists while he was not yet too old.(2) The author Jocelyn Brooke observed:

It is a curious fact that the numerous extant portraits of Firbank bear almost no resemblance to each other, seeming indeed, to depict a series of entirely disparate persons. During his life he was drawn or painted by Charles Shannon, Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis, Alvara Guevara and probably (for he was fond of sitting for his portrait) by other artists as well; yet it remains extraordinarily difficult to form an exact mental picture of his features.

Even the three portraits Augustus John did of Firbank might just as well have been portraits of three different people: they look like a businessman, or a witty theatre-goer, or an intimate, somewhat sad friend. Shannon's portrait is that of a cautious and gentle observer.

Brooke continues:

His profile was delicately formed and angular, with a finely-arched nose, a full-lipped mouth and a rather weak chin; his eyes were greyish-blue tending to blue, his hair dark and inclined to to be tousled, his complexion fresh, with a rosy tint about the lips and cheekbones which perhaps owed more to Art than to Nature.(3)

Firbank was tall, slender, 'inclined to droop', and in society he behaved extremely shy. Augustus John remembered:

[...] he sent his taxi-man in to prepare the way, himself sitting in the taxi with averted face, the very picture of exquisite confusion. [...] When the strain of confronting me became unbearable, he would seek refuge in the lavatory, there to wash his hands. This manoeuvre occurred several times at each sitting.(4)

Did Firbank present himself in the same way to Shannon's studio in 1909 - if it was indeed 1909? Did he behave in the same awkward manner, or was he less nervous in the company of the quiet and silent painter?

Ifan Kyrle Fletcher reported that Firbank 'entertained very exquisitely' in his room that was 'decorated with masses of white flowers':

Often, on these occasions, Firbank talked little, but, if he had recently been to London, he would be full of news of pictures by Shannon and Ricketts, concerts of the music of Granados and Debussy, new French books and plays.(5)

It is not known whether Firbank acquired paintings, drawings or lithographs by Shannon or Ricketts. What is known is that, after his portrait was drawn, he sent Shannon copies of his books, at least of Vainglory (1915) and Inclinations (1916).

Because another illustration was not available for his last book, he illustrated the dust jacket with Shannon's then fifteen-year-old portrait, and for the frontispiece he selected one of the old portraits by Augustus John. In her biography, Benkovitz commented: 'Death haunted neither portrait; in them Firbank had his youth again.'(6)

Around 1929, a fellow Firbank student, A.C. Landsberg, recalled Shannon's portrait:Wednesday, June 1, 2022

565. Ricketts & Shannon at the Technical School of Art (2)

The previous blog with new data on the schooling of the artists of The Vale (written by Anna Gruetzner Robins) prompted John Aplin to delve into the archives once again. An uncredited memoir from the collection of the Senate House in London was probably written by Arthur Hugh Fisher (1867-1945), who remembered the days at the Lambeth School of Art:

The school occupied two buildings at half a mile distance from each other. One was in a narrow alley off Upper Kennington Lane and there were held classes for drawing from casts of the antique and classes for study of perspective. At the other, in Kennington Park Road, were the life classes and the modelling school. Among the students at that time were [Sturge] Moore's great friends Charles Ricketts and C.H. Shannon and those admitted to their intimacy, Reginald Savage and [A.J.] Finberg.