|

| 12, Edith Grove, Brompton (in later years) |

|

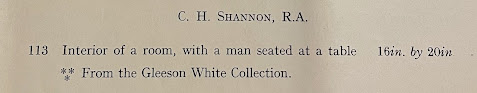

| Catalogue Sotheby & Co., 29 March 1939: description of 'Interior of a room, with a man seated at a table' |

|

| 12, Edith Grove, Brompton (in later years) |

|

| Catalogue Sotheby & Co., 29 March 1939: description of 'Interior of a room, with a man seated at a table' |

After the publication of last week's blog, 'A Sketch by Charles Shannon', the new owner of Shannon's drawing contacted me. Thanks for that, Michael Seeney, and congratulations.

He provided additional information about the condition of the drawing and sent an image of the back of the frame with the gallery's label that unfortunately gives little information: no year or catalogue number, or previous owner, but only the name and years of the maker and the address of the gallery.

|

| Charles Shannon, sketch of a woman brushing her hair (undated) [Collection Michael Seeney] |

The Ruskin Gallery Ltd. was located in 11 Chapel Street, Stratford-on-Avon [for an image of the building see British Listed Buildings], and definitely still active in the 1960s.

Seeney's account of the condition is as follows:

"I took the picture out of the frame and the sheet is unfortunately laid down on backing board; there is no signature but the right hand long edge of the sheet is perforated, I assume from being detached from a sketch book. The paper is very thin, but without being able to lift it from the backing means I can give no more information." |

| Charles Shannon, sketch of a woman brushing her hair (undated) |

For the first issues of the weekly Black and White a masthead (or nameplate in American English) was designed by Charles Ricketts in 1891. Due to the complexity of the drawing, in which the title almost seemed to be hidden, it was only used for a short time.

.jpeg) |

| Charles Ricketts, masthead for Black and White, 1891 |

Of course, the title had to be immediately legible and recognisable, even from a distance, in order to speed up the sale of individual issues. There were probably complaints about Ricketts's masthead, and a more straightforward (anonymous) drawing was made. [Read about this masthead and its replacement in blog 45: Lux, Ars, Spes, and Night.]

Black and White was an expensive production and of course had to sell well, targeting an international audience, or at least British citizens visiting other countries. It was on sale at Neal's English Library in Paris, at Saarbach's American Exchange in Mainz, and could be bought in the USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

However, it is quite possible that Ricketts had already drawn other advertising material for the weekly magazine before his masthead was rejected for prolonged use. The issue of 23 April 1892 includes an image of a sales booth at Venice, London, Olympia, that seems to confirm this.

|

| 'Black and White' stall at Venice in London, Olympia Black and White, 23 April 1892, p. 543 |

'Venice in London' was a spectacular indoor aquatic show at Olympia opened on 26 December 1891, and attracting huge crowds for more than three years.

|

Venice in London, souvenir programme 1891-1892 [Collection V&A, London] |

There were canals and buildings that represented the Rialto Bridge, shops, glass-blowing manufactories, Venetian pleasure gardens, thirty specially made (shorter) gondolas, serenades, concerts, and a 'Grand Aquatic Carnival Ballet' with a thousand dancers. A 'Majestic Aquatic Pageant' was presented four times a day. [Read V&A curator Cathy Haill's blog about the event.]

The organisers needed £60,000 for this spectacle and advertising revenue was more than welcome. This was the ideal place to attract more customers for any product, and Black and White magazine must have paid a nice sum of money to set up a sales stall there.

|

| 'Black and White' stall at Venice in London, Olympia (detail) Black and White, 23 April 1892, p. 543 |

The lettering with the long tail of the 'R' for record and a similar but different tail of the 'R' for review, but especially the idiosyncratic shape of the letter 'C' after which the letter o is drawn as an afterthought, as well as the slightly to the left tilted ampersand look very much like Ricketts lettering in those years.

|

| Charles Shannon, 'Portrait of Charles Ricketts, painted at Kennington Road, Lambeth', before 1900 |

In February and March 1905, Ricketts and Shannon enjoyed vacations in Rome and Florence, and in August of that year they kept it closer to home. They bivouacked on the English coast for a prosaic reason: their house at Lansdowne Road was being painted. Their accommodation was The Albany Hotel, that curves around Robertson Terrace in Hastings. The hotel had opened in 1885 under the name Albany Mansions.

|

| Albany Mansions, c.1890 |

|

| The Albany Hotel, 1906 |

During the summers, art historian Mary Berenson, who lived with her husband Bernhard Berenson at Villa I Tatti near Florence, visited her mother in London, and during her 1904 stay she visited Charles Ricketts.

|

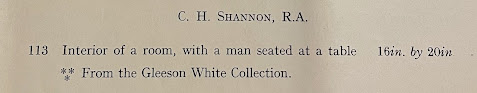

| Mary Berenson by unknown photographer: (matte printing-out paper print, circa 1893) [© National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG Ax160669] |

Ricketts and Shannon visited Venice at least three times, beginning in 1899, then in 1903 and in 1908; on the latter occasion staying at the House of Desdemona on the Grand Canal owned by their friends Edmund and Mary Davis, and more commonly known as the Palazzo Contarini Fasan.

|

| Paolo Salviati, photo of Palazzo Contarini Fasan, c. 1891-1894[detail] [Boston Public Library: William Vaughn Tupper Scrapbook Collection] |

On August 9, 1911, a heat record was set in the United Kingdom: a temperature of 36.7 degrees Celsius was recorded for the first time in history. The previous letter in this summer series (Purgatorial London) was set during the same heat wave, but focused on domestic scenes. In this letter, the world beyond is brought in.

|

| Louis Béroud, 'Mona Lisa au Louvre' (1911) [Wikimedia Commons] |

The letter is addressed to Mary Davis, artist and wife of Edmund Davis who had commissioned the building of Lansdowne House for a number of artists including Ricketts and Shannon. It was from this flat that Ricketts wrote the letter to Davis, who was apparently traveling and thus provided with Ricketts's version of some news.

A lot had happened.

On July 20, the newspapers reported that Herbert Trench had resigned as director at Haymarket Theatre. There were many strikes that year, including those of railroad staff, which brought transports to a standstill, caused shortages in stores, which caused prices to rise, and drove housekeepers to despair - like Ethel, the loyal servant of Ricketts & Shannon (who continued to work for them until 1923). On 18 August, the House of Lords was forced to pass a new Parliament Act to curb its power. On 21 August, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre; on 26 August, reports circulated that the director of the Louvre, Théophile Homolle would be fired, as, indeed, he was, two days later.

Shannon had to go to some meeting at the R A, at the door he was asked his business and name.

Your name Sir?

Shannon

O, I am Mr Shannon!

Attendant

The summer of 1911 was hot. Edith Cooper and her aunt and lover Katharine Bradley - their nom de plume was Michael Field - had fled London and were staying in a cottage near Armitage near Hawkesyard Priory, before spending three weeks in Malvern. They enjoyed the attention not only of the prior, but also of the Dominican novices, especially Brother Bruno and Brother Bertrand. In their diary they noted the constant heat, while 'the cedars are loaded with aroma'. Brother Bertrand swam the lake to bring them 'a glorious armful of yellow waterlilies' (see 'The Diaries of Michael Field', August, 1911, at the online edition at Dartmouth College). In one of his letters, Ricketts responds to the company of young men surrounding Michael Field.

|

| Charles Shannon, portrait of Edith Cooper, 1900-1910, black and red chalk drawing, touched with white on brown paper [Birmingham Museums: 1914P246] |

Heat waves and holiday traffic jams - it's time for an anthology of Charles Ricketts's letters with references to heat, summer and holidays.

This first letter in the short series was written to artist Thomas Lowinsky (1892-1947), who had attended the Slade School of Art in London before the Great War, and at the time of this letter was serving in the Army of Occupation, stationed in Cologne, before being demobilised in April 1919. The date is uncertain, but the letter probably dates from January 1919. Here are some excerpts from this letter, including a fantasy of a tropical destination.

|

| Eric Gill, portrait of Thomas Lowinsky, 'Thomas Esmond Lowinsky', wood engraving, 1924 [National Portrait Gallery: NPG D5127] |

In 1928 Robes of Thespis: Costume Designs by Modern Artists, a book on modern costumes for plays, revues, operas and ballet, was published. It included seven costume drawings by Charles Ricketts (only one of which was in colour) for 'The Merchant of Venice', 'King Lear', 'The Winter's Tale', and Yeats' 'King's Threshold'. Ricketts was no longer a 'modern artist' in 1928; the hefty book focused on a younger generation. More interesting than the commentary on his costumes is the illustrated introduction by Max Beerbohm.

Beerbohm had lived in Rapallo since 1910, but, he was briefly back in London in 1925. From a taxi, he saw Ricketts and Shannon walking in the street, apparently on their way to the opera:

[...] though I waved my hand wildly to them they did not see me. An any rate, Shannon did not. Ricketts may have, perhaps, and just ignored me. For I was not wearing a top-hat. And Ricketts was.

It was an opera hat - 'a thing that opens with a loud plop and closes with a quiet snap'. Beerbohm remembers the days in the 1890s when he himself always wore a top hat - and Ricketts and Shannon did not. And now that nobody wore top hats anymore, Ricketts did.

I wonder, does Ricketts wear that collapsible crown of his only when he dines out? Or does he, when he comes home, close it with a quiet snap and place it under his pillow, ready for the first thing in the morning? Some painters wear hats when they are working, to shade their eyes. Does Ricketts at his easel wear his gibus?

The answer is no. Rickets painted bare-headedly.

Beerbohm then turns to the use of colour in clothing and laments the fact that since 1830, men's fashion has turned into the tyranny of black and white. Only on stage did the colours shine, at least since 1900, when Gordon Craig and Ricketts designed costumes. Still, the stage designers themselves, walk around in black and white. Beerbohm made a drawing to show it: William Nicholson, Albert Rutherston, Edward Gordon Craig, R. Boyd Morrison and Charles Ricketts - only the last three are shown below.

|

| Max Beerbohm, 'Here are Five Friends of Mine' [Detail] (from Robes of Thespis, 1928) © Copyright of the Estate of Max Beerbohm |

I have given Ricketts the small sombrero that I had always associated with him. When one does a drawing, what is one glimpse as against the vision of a lifetime?

Beerbohm understands young people's desire for colour and fantasy and believes that stage designers should set a good example.

I appeal to the designers of theatrical costumes. Doubtless they have hoped that the orgies of colour and fantasy with which they grace the theatres would have a marked effect on the streets, instead of merely making the streets' effect duller than ever by contrast. I suggest to these eminent friends of mine that they should design costumes not merely for actors and actresses, but also for citizens. [...] Let them go around setting the example. This is a splendid idea. I am too excited to write about it. I will do another drawing.

|

| Max Beerbohm, 'Why Not Rather Thus?' [Detail] (from Robes of Thespis, 1928) © Copyright of the Estate of Max Beerbohm |

Ricketts now looks like a courtier from the Renaissance, his preferred period, with colourful rings on his fingers, a straight high feather on his cap, a green tunic and tights in blue and white. He also carries a sword.

It is fortunate that Ricketts did not carry a sword in real life.

|

| Charles Shannon, 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' (woodcut, proof) British Library, London: 1938,0728.9 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

|

| Charles Shannon, Sketch of Mercury/Hermes for Hero & Leander (red chalk drawing) British Library, London: 1938,1008.31 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

|

| Charles Shannon, Sketch of one of the Fates for Hero & Leander (red chalk drawing) British Library, London: 1938,1008.30 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

|

| Charles Shannon, 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' (original drawing) [from the collection of Vincent Barlow] |

|

| Charles Ricketts or Charles Shannon, Preparatory drawing for 'Hermes Disdains the Amorous Destinies' British Library, London: 1946,0209.89 [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license] |

|

| Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450-1900 (1929: second edition) |

|

Rembrandt van Rijn and (mainly) workshop, 'Portrait of a Woman with a Fan', 1643 |

|

| Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450-1900 (1929: second edition), p. 228, No. 589: 'Christ as Emmaus' |

|

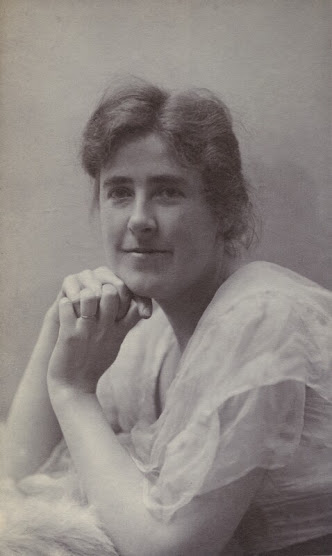

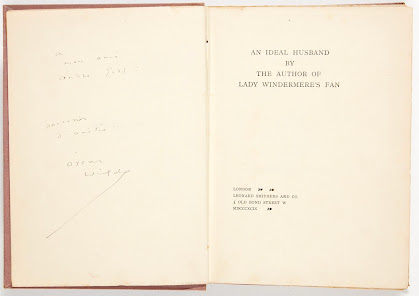

| Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband (1899): autograph dedication to André Gide |