There are many types of book collectors. Some strive for completeness; others settle for a representative selection; some follow fashions, others their own passion; some focus on deluxe editions; others on literary curiosities or series of pocket books; some collectors can financially afford whatever they like, others have small purses.

A number of British collectors of Vale Press editions will be featured over the next few weeks. I begin this short series with an exceptional collector: we know almost nothing about him and the sparse trivia about his life and collecting tendencies are drawn from only one source: his obituary.

James Dunn, a shy collector

Dunn died in December 1943 in Blackburn where he was born in 1867. His wife, Clara Dunn (born Cott) died in 1907, aged 35. His son Ernest emigrated to South Africa around 1918, and his daughter married a Trevor Simpson and moved to Wrightington near Wigan.

|

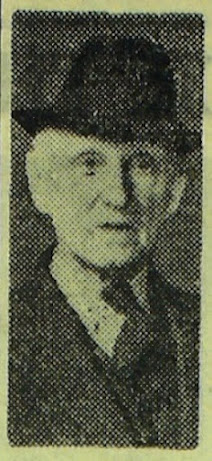

| James Dunn (Northern Daily Telegraph, 16 December 1943) [published on Cotton Town Blackburn with Darwen by Philip Crompton, 2019] |

For much of his life - between the two world wars - he lived alone. Perhaps that is why he spent his time reading books and came to be a collector. Reading was a form of self-education. Dunn came from a poor family and had no formal training. After primary school, he was employed and at 14, he was a cotton piecer (1881 Cencus). His father ran a big drapery shop in Montague Street. According to an advertisement, his was the 'best and cheapest house' for general drapery, oilcloths, linoleums, mattings, carpets, rugs and more. As the eldest child, James Dunn continued this business in the working-class area of Blackburn.

|

| Dunn household based on 1881 Cencus |

Reading was not his only passion. A second pastime was walking - he walked, for example, from his home to Blackpool, over 40 kilometres, or to his daughter's house. But he also made trips to North Africa where he walked from village to village, probably in the then French territories of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. He had taught himself French.

In Paris, he explored the many bookstores and antiquarian bookshops, and in order to properly assess what he wanted to buy, he had begun to learn the country's language when he was older. His obituary said he not only could read French well, but also spoke it fluently (we do not know who in Blackburn could judge the level of quality of his French).

In the early years of World War II - he was already in his 70s - he developed a third craze: he regularly travelled to London to witness air raids. Incidentally, this sensationalism also existed during the First World War, when he travelled far and wide to spot a zeppelin or see the effects of a bombing raid with his own eyes.

The James Dunn Collection

Only a single photograph is known of Dunn - it accompanied his obituary. Family papers do not seem to have survived, nor a photograph of Dunn at the Eiffel Tower or on a Moroccan beach. His public profile was limited, Dunn shunned publicity, but he was, however, a trustee of the Primitive Methodist Church (old Montague Street).

As an autodidact, Dunn will no doubt have made use of Blackburn's public library, and after getting his collection of books together, he took a remarkable step and wanted to bequeath the collection to the Blackburn's Library, Museum, and Art Gallery.

|

| Lancashire Evening Post, 17 October 1940 |

On 17 October 1940, the Lancashire Evening Post reported that the Blackburn Public Library Committee had decided to accept the gift of 'part of his collection of fine and rare books'. From then on, rows of books moved from his home to the library, not all at once, but in portions. His Vale Press books, for example, were donated between November 1940 and April 1942, as evidenced by the labels recording the gift in the books.

Some links to the John Dunn Collection:

- Philip Crompton, 'The Dunn Collection. Finding the needles in the haystack', Cotton Town, Blackburn with Darwen, April 2019.

- Philip Crompton, 'Oil Paintings in the James Dunn Collection', BM&AG blog, 27 May 2020.

- Cynthia Johnston, 'The James Dunn Collection', BM&AG blog, 26 May 2020.

- Interview with Cynthia Johnston, 'A Life Less Ordinary. The Elusive Mr Dunn', 'Tales from the Collection. Blackburn Museum at You Tube, 19 March 2022.

.jpeg)